Science denialism is a form of pseudoscience. The term pseudoscience has been the object of a renewed interest by philosophers of science in recent years. This is not just because the so-called demarcation problem—the question of what distinguishes science from pseudoscience—is inherently interesting to philosophers and epistemologists. It is also because pseudoscience matters, as in the case of the increasingly clear negative personal and societal effects of, for instance, vaccine and climate change denialism. But is denialism the same thing as pseudoscience? What do people who reject the notion of evolution, say, have in common with people who push homeopathic “remedies”? My colleague Sven Ove Hansson of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm has written an insightful paper about this (Hansson 2017). [Hansson also wrote “The Hidden Connection between Academic Relativists and Science Denial” in the September/October 2021 Skeptical Inquirer.—Eds.] Hansson begins by distinguishing two kinds of bad epistemic practices that fall under the broader umbrella of pseudoscience: science denialism and pseudotheory promotion. The former includes denial of evolution, climate change, vaccine efficacy, etc. The latter has to do with homeopathy, astrology, ancient astronaut theories, and so on. … (Skeptical Inquirer)

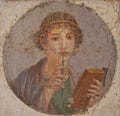

Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance. (Book review) In this book Christopher Gill offers a robust defense of Stoic ethics. He calls into question a number of common and stubbornly persistent misconceptions of Stoicism, and the account that emerges may strike some as unexpected, even provocative. Among other things, he argues that Stoicism has a lot to offer modern virtue ethics and that, in many respects, Stoic ethics is more coherent and cogent than Aristotle’s ethics. The book, while no doubt of interest to specialists in ancient philosophy, has much wider ambitions and aims to make a contribution to contemporary ethical debates. As such, it has the potential to be of interest to a wide philosophical audience. The book divides into three parts. The first part (chapters 1–3) sets out the core ideas in Stoic ethics. The second part (chapters 4–5) examines Stoic accounts of ethical development. The third part (chapters 6–8) considers the role that Stoic ethics might play in contemporary ethical debates, within both academic discussions of virtue ethics and popular life guidance and self-help. … (Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews)

The New Hellenism. Academic philosophy had reached a pretty pass by 2010. In the previous decade, many of the most eminent figures of the late 20th century—including Willard Van Orman Quine, Richard Rorty, Jacques Derrida, Pierre Hadot, Donald Davidson, David Lewis, Jean Baudrillard, Bernard Williams, Hans-Georg Gadamer, John Rawls, and Paul Ricœur—had departed for parts unknown. Both analytic and continental philosophy had long been in a period of codification and refinement rather than wild creativity or revolutionary overturning. No one was anticipating the thunderclap arrival of the next Wittgenstein or Heidegger; everyone seemed content to qualify or apply the results of their predecessors, and re-air the debates among them. Like other disciplines, and more thoroughly than most, philosophy seemed to have been successfully professionalized and contained within academia. Most of the work published in journals in almost any style was relatively inaccessible to nonspecialists. By 2010, the jargons of continental and analytic philosophy had been elaborated and refined for a century. Philosophers couldn’t speak even to one another, let alone communicate with the public. Among other things, this might have made it hard to attract students. And if you can’t attract students, administrators won’t hire professors. … (LA Review of Books)

Why novels are a richer experience than movies. Novels solve what philosophers call “the problem of other minds.” It’s the problem that we can never know for sure what a person is thinking, or, from a metaphysical perspective, if they even have a mind at all! We must infer, we must guess, we must speculate. Novels, however, take place in an imaginary world where the problem of other minds does not exist, where mental states, like rage or ennui, can be referred to as directly as one does tables and chairs. There’s an entire academic field that highlights this, like Dorrit Cohn’s Transparent Minds, published in 1978, in which she emphasizes that this is “the singular power possessed by the novelist: creator of beings whose inner lives he can reveal at will.” Or as another scholar put it: “Novel reading is mind reading.” … (Nautilus)

Inventing skeptical language. Language is shorthand. We use words to signify complex concepts that are mutually understood. The word car, for example, is easily comprehended by all people in a conversation because we’ve all seen cars, have been in cars, and many of us have driven a car. This shared lexicon makes communication easy because we can convey quite complex concepts in just a few words, sometimes just a single word. The need to convey complex concepts often arises in my practical skeptical activity. The same false beliefs and misunderstandings come up again and again, so I find myself giving the same explanations again and again. Sometimes I’m trying to explain an existing phenomenon that does not have a common descriptor. Sometimes I’m presenting an idea of my own that does not yet have a name. … (Skeptical Inquirer)

I'll try that!

There is an issue you haven't mentioned in your article. You cite Hanson: "its proponents actively attempt to create the impression that the statement is highly reliable in its own domain". And one way they do this and it catches many of us on the wrong foot is through respectable (*) scientists who drift into other fields and on the basis of their good rep cause havoc. I had an evolution denying statistics professor, Newton had a side line in alchemy, and among climate change deniers and vakskeptiks a number of those people thrive (for visibility, speaking gigs, attention?)

(*) once respectable :)

Nice recommendations/selections 👍