Philosophy as a Way of Life—III—Socrates and the finest state of the human soul

Why the sage from Athens has inspired people through the millennia

[Check out parts I and II of this series.]

I’m going to bet that it is going to be hard to find anyone who has never heard of Socrates. Even in this world of social media and alternative realities the name of Socrates is essentially synonymous with philosophy. Which doesn’t mean one necessarily knows anything about the sage of Athens, or about philosophy. (Which is fair enough. I can name Taylor Swift, for instance, but not a single one of her songs…)

Pierre Hadot, in his influential Philosophy as a Way of Life is interested in Socrates, not necessarily the historical person, about which it is hard to say much anyway, but the philosophical figure, which has become a symbol for philosophy itself.

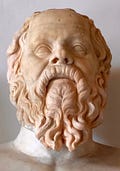

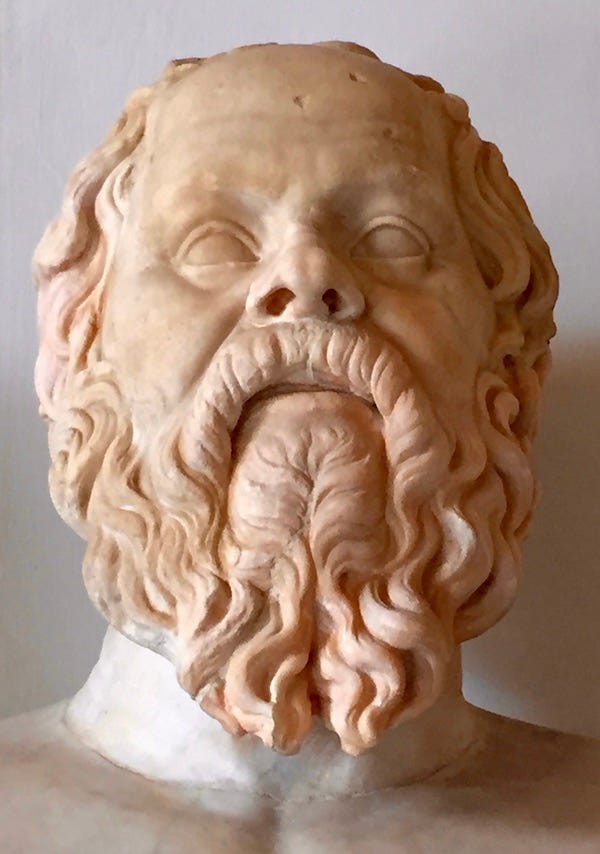

He begins with his (alleged) physical appearance. Socrates was ugly, by universal agreement of all the available sources: Plato, Xenophon, and Aristophanes. As Nietzsche put it: “Everything in him is exaggerated, buffo, a caricature.” (Twilight of the Idols. The Problem of Socrates, 3-4) Hadot writes:

“Alcibiades, in his famous speech in praise of Socrates at the end of the Symposium, compares Socrates to the little statues of Sileni [a kind of ugly satyr] that could be found in sculptors’ shops, which concealed little figurines of the gods inside themselves. Similarly, Socrates’ exterior appearance—ugly, buffoon-like, impudent, almost monstrous—was only a mask and a facade.” (p. 148)

And it wasn’t just his physical appearance. Socrates often behaved like a buffoon, pretending to be naive and not too bright. In Plato’s Symposium, Alcibiades says: “He spends his whole life playing the part of a simpleton and a child.” (216e)

Like children do, Socrates famously went around asking questions to people. But unlike those of a child, his questions were only superficially simple. The goal was not to obtain knowledge, but rather to trigger aporia, or confusion, in his interlocutors, so that people started doubting whether they really knew what they were talking about (usually, they didn’t). If they got to the point of admitting their ignorance that was their first step toward wisdom. Know thyself, was the injunction of the Oracle at Delphi, and the starting point of self-knowledge is awareness of our own limitations.

After Socrates died, a whole literary genre arose, known as logoi sokratikoi, where the authors imitated the Socratic style and method. In these dialogues, Socrates himself appeared as a prosopon, a character, or mask. But one can argue that Socrates was already a character in Plato’s own dialogues, which is why it is so difficult to distinguish Plato’s philosophy from that of his teacher, an issue that scholars have labeled the Socratic problem.

Be that as it may, from a pedagogical perspective Socrates understood that one is not very effective by directly telling people the truth. In a sense, they have to be deceived into arriving at the truth themselves. Not through one-sided lectures, but through what we today call the Socratic method. That’s why Socrates presented himself as a philosophical midwife:

“I am like the midwife, in that I cannot myself give birth to wisdom.” (Plato, Theaetetus, 148e)

But that famous image is itself deceptive. While Socrates goes on in the Theaetetus to say that he doesn’t really have any wisdom, which is why he cannot transmit it to others, that’s plain nonsense. Even a superficial examination of the Socratic dialogues shows that Socrates knows very well were he wants to nudge his interlocutors. But he has to pretend not to know anything, so that they lower their guard and willingly let the midwife do his job. Nietzsche again:

“An educator never says what he himself thinks, but always only what he thinks of a thing in relation to the requirements of those he educates. He must not be detected in this dissimulation.” (Posthumous Fragments, June-July 1885)

There is no doubt that Socrates’ self-deprecation was feigned, and this was clear already in antiquity. Just ask Cicero:

“By disparaging himself, Socrates used to concede more than was necessary to the adversaries he wanted to refute. Thus, thinking one thing and saying another, he enjoyed using the kind of dissimulation which the Greeks call ‘irony’.” (Lucullus, 15)

But why would a teacher engage in this sort of sustained deception of his students? Because teaching is not a process of filling up otherwise empty minds with the wisdom and knowledge of the teacher. It’s about the student learning how to think. The Socratic approach makes it possible for the pupil to experience in the first person what the activity of the mind consists of, what we refer to as critical thinking. The goal, again, is not knowledge, but mindful doubt. It’s about the process, not the result.

Interestingly, in Xenophon’s Memorabilia there is a bit where the Sophist Hippias loses his patience with Socrates and says that he (Socrates) would do well to stop asking questions about justice and, once and for all, just tell us what justice is. To which Socrates responds: “If I don’t reveal my views on justice in words, I do so by my conduct.” (Memorabilia, IV.4.10)

Socrates is very conscious of his chosen mission in life. He states it explicitly in Plato’s Apology:

“I care nothing for what most people care about: money-making, administration of property, generalships, success in public debates, magistracies, coalitions, and political factions. … I did not choose that path, but rather the one by which I could do the greatest good to each of you in particular: by trying to persuade each of you to concern himself less about what he has that about what he is, so that he may make himself as good and as reasonable as possible.” (Apology, 36b)

I just love the notion of becoming concern less with what we have and more with who we are. Again, “know thyself,” not “own as much crap as possible.”

According to Nietzsche (in Posthumous Fragments, April-June 1885) Socrates’ “irony,” that is, passing himself for a simpleton while he was nothing of the kind, was what gave him access to people from all walks of life. They opened up to him because he wasn’t pretentious and did not appear intellectually threatening.

It must be noted that Socrates did not establish a philosophical school. He didn’t build something like Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, Epicurus’ Garden, or Zeno’s Stoa. Hadot comments (p. 157) that his philosophy was a spiritual exercise, an invitation to a whole way of life founded on active reflection and conscious living.

Famously, in the Symposium, Socrates and Alcibiades refer to what they are experiencing as eros, but the word has two very different meanings. One is the standard connotation of erotic love, which modern English has inherited; the other is love of beauty and wisdom. As a result of his love for Socrates, Alcibiades turns out to be in a wretched condition, as he says himself:

“I am the one who has been reduced to slavery, and I’m in the state of a man bitten by a viper. I’ve been bitten in the heart, or the mind, or whatever you like to call it, by Socrates’ philosophy. … The moment I hear him speak I am smitten with a kind of sacred rage, … and my heart jumps into my mouth and the tears start into my eyes. I’m not the only one, either; there’s Charmides, and Euthydemus, and ever so many more. He’s made fools of them all, just as if he were the beloved, not the lover.” (Symposium, 217-222)

Obviously, Alcibiades is in love with Socrates’ wisdom, not his physical appearance—since he’s very ugly. Nevertheless, Alcibiades confuses the two meanings of eros and concocts a scheme to have sex with Socrates by spending the night on the same couch. But Socrates behaves like a brother to Alcibiades, not allowing himself to be lured by the youth’s stunning physical beauty. Stunningly, the attraction Alcibiades, Charmides, Euthydemus and others had for Socrates spanned the centuries. In 1772 Goethe wrote in a letter to a friend: “If only I could be Alcibiades for one day and one night, and then die!”

It is hard to find a better way to end this essay, and at the same time express my hope for the future of philosophy, than by transcribing what Nietzsche wrote about Socrates in Human, All Too Human:

“If all goes well, the time will come when one will take up the Memorabilia of Socrates rather than the Bible as a guide to morals and reason. … The pathways of the most various philosophical modes of life lead back to him. … Socrates excels the founder of Christianity in possessing a joyful kind of seriousness and that wisdom full of roguishness that constitutes the finest state of the human soul.” (§86, vol. 2, pp. 591-2)

Amen.

[Next in this series: Only the present is our happiness.]

What would be the moral progress for non sages? Can it only be determined on the rack? Or would minimizing suffering qualify as progress?

“Wisdom’s” potency in and of itself hinges upon the act of “not being claimed” as a possession or object.

This insight is what unleashes the power to liberate for those who “love” wisdom. And as a consequence — for it’s unparalleled freedom that is experienced — this propels a person into a state of “awe” and wonder at the “marvel” that permeates the mind in it’s quest to know it.

Also, this portrayal of Socrates as a buffoon to disarm his audience while he engages in dialogue with them in the marketplace might have been gleaned from his experience in the Peloponnesian war where he demonstrated to friend and foe, just what a formidable warrior he was during a serious crisis such as armed battle.

Socrates knowing both sides of the coin and discovering for himself this deep love of wisdom gave him the skill to be dexterous in his personality that allowed him to act as a fool while his inner fortitude is that of a warrior.