[Based on How to Grow Old: Ancient Wisdom for the Second Half of Life, by Cicero, translated by Philip Freeman. Full book series here.]

You know when you are having a really, really bad year? Most of us would probably think of the recent covid pandemic, or perhaps of a time when we lost a job or, worse yet, a loved one. Marcus Tullius Cicero knew something about having a bad year. One of his worst was 45 BCE, when he was 61.

Four years earlier Julius Caesar had crossed the river Rubicon with one of his legions, thus declaring war on the Senate of Rome. The ensuing civil war had seen Cicero fighting on the losing side against Caesar, which prompted him to retire from political and public life (forever, he thought, though he turned out to be wrong). Moreover, Cicero’s beloved daughter, Tullia, died in childbirth aged 33.

Cicero was devastated, affected by unrecoverable losses on both the public and the private fronts. And he was getting old, by Roman standards. However, he reacted with force to his new predicament. He did not commit suicide, as his colleague Cato the Younger had done after his defeat by Caesar. And he did not turn to Epicureanism and a hedonic life, like his closest friend Atticus had done many years previously. Instead, he pulled himself up from the depth of despair by writing philosophical treatises.

One such book was On Old Age, which has become a perennial classic. Michel de Montaigne read it and said that it made him look forward to growing old. John Adams re-read it several times in his own old age. And Benjamin Franklin printed a translation of it in English in 1744. Philip Freeman has issued a new translation for Princeton Press’s Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series, and its well worth checking it out.

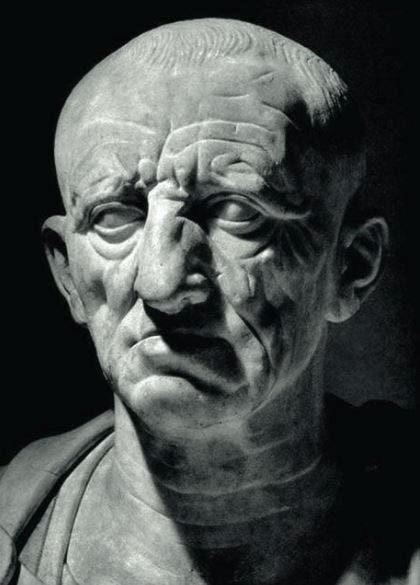

On Old Age takes the form of a dialogue among three characters: Cato the Elder (the great-grandfather of the above mentioned Cato the Younger), Scipio Aemilianus and Gaius Laelius Sapiens. Cato was an excellent choice for a book on old age, since he died at 85 in top physical and mental form. Scipio was a Roman general and statesman known for his exploits during the Third Punic War against Carthage, while Laelius became Consul in 140 BCE. A distinguished company, you might say.

In the book, Cicero provides ten pieces of timeless advice about growing old. Here they are:

I. A good old age begins when we are young. This is advice we also get from modern medicine and psychology: we need to cultivate good habits early on in life, so that they will continue to benefit us later on. These include temperance, clear thinking, and wisdom. As Freeman, the translator, puts it, miserable young people do not become happy just because they get old…

II. Old age can be an enjoyable time in our life. So long as we have developed the proper internal resources, there is no reason—save for disease (which, of course, may strike at any age)—we shouldn’t be able to enjoy our later years. Yes, there are plenty of unhappy old people, but Cicero argues that that’s the result of their character, which was formed early on, not of age per se.

III. Life has proper seasons. When we are young most of us don’t wish to revert back to childhood, because we appreciate that those are different moments in a natural lifespan, each characterized by its own advantages and limitations. The same goes for old age, if we pay proper attention to it. It is therefore a mistake to cling to a more youthful look, as we are constantly told we should do by an industry that makes tons of money by selling us absurd notions like “60s is the new 40s.”

IV. Older people can teach young ones. Generations can fruitfully help each other. There is much delight that old people can find in the company of younger ones, but that goes the other way around as well. Although we live in a society that shows increasing disdain for the elderly, they have much to teach us, in terms of life experience, if we take the time to listen.

V. We can pursue an active life in old age. Old people are unlikely to compete with younger ones in terms of physical activities. But mentally, as far as both knowledge and wisdom are concerned, they have much to contribute to society. Again, it is a matter of recognizing the strengths and limits of each age. We neither expect a 20-year old to be wise nor a 70-year old to compete in the Olympics.

VI. The mind is a muscle, metaphorically speaking. Our mind can be exercised throughout our life and thus be far more likely to serve us well in old age. Plenty of modern medical research confirms Cicero’s insight here: learn to play a musical instrument, or to master a new language, or simply keep reading and be engaged and you are far more likely to stay sharp as the years go by.

VII. Old people must stand up for themselves. Even though the ancient Romans had a lot more respect for the elderly than we do nowadays, it was true then as it is now that older people have to assert themselves and demand attention and care. The later years of our life are not a time for passivity.

VIII. Sex is overrated. A common complaint about old age is that one’s libido decreases, and so does the enjoyment of a number of other sensual pleasures, including drinking and eating. Good!, says Cicero. That way we can focus our attention on other things, like reading, writing, learning, and conversing. Besides, we may no longer have the lust for pleasure that we had when we were young, but we have far more experience and discernment, which helps us enjoy those pleasures in a more refined fashion.

IX. Cultivate your own garden. Cicero means this literally, and devotes a section of De Senectute to the joys of farming. But if spreading manure and pruning grapevines is not your cup of tea the point is to find a meaningful and pleasurable activity (or activities) that engages you when old. This isn’t a question of keeping busy for busyness sake, but of feeling alive because one is enjoying life.

X. Death is no big deal. As essentially a Stoic, Cicero maintained that death—which is in the proximity of old age, statistically speaking—is not to be feared. There are two possibilities after we die: nothingness, or a new life. In the first case, why worry, since we will literally not be “there” to worry about anything at all? In the second case, yay, a bonus!

The following are some highlights from How to Grow Old, with accompanying brief commentaries:

“Those who lack within themselves the means for living a blessed and happy life will find any age painful. … Everyone hopes to reach old age, but when it comes, most of us complain about it.” (4)

I love the sarcastic comment made by Cato, about everyone wanting to get old and then complaining about it. It is so true. But the main point of this passage is that a lot depends on our own inner resources, and especially on our attitude toward things. This is true for old age as for anything else in life.

The idea isn’t the pollyannaish one that all we need to do is to think positively and things will be fine. Things are what they are, but whether they are “fine” is a human judgment. That is why people react differently to the same exact situation. As Epictetus puts it in a different context, death can’t be so bad because otherwise it would have seemed so to Socrates. Cicero could say the same of old age: it can’t be as bad because otherwise it would have seemed so to Cato the Elder.

That said, Cicero does not ignore the fact that some people are more lucky than others. At one point in the dialogue Cato acknowledges his “privilege,” as we would put it today, saying that he got lucky, in certain respects. But the point remains: if our attitude is a bad one than even the most objectively splendid old age will appear full of misery.

“People who say there are no useful activities for old age don’t know what they’re talking about. They are like those who say a pilot does nothing useful for sailing a ship because others climb the masts, run along the gangways, and work the pumps while he sits quietly in the stern holding the rudder.” (17)

Nice metaphor. There is more than one way to evaluate one’s usefulness and level of activity. And if we apply the wrong criteria to a given situation we may conclude that ship pilots have nothing important to do because, after all, they just sit there and let others do the real work.

There are at least two underlying principles to note here: first, the division of labor between younger and older people. Second, the notion that different ages are more suitable for different kinds of contributions to society. And of course the two principles are interrelated: it is because young and old people are more apt to do one thing rather than another that it makes sense for society to make optimal use of both. To build on Cicero’s metaphor: don’t waste the captains’ expertise and make him climb the masts, and don’t put a dangerously inexpert young sailor at the helm of the ship.

“We must fight, my dear Laelius and Scipio, against old age. We must compensate for its drawbacks by constant care and attend to its defects as if it were a disease. We can do this by following a plan of healthy living, exercising in moderation, and eating and drinking just enough to restore our bodies without overburdening them. And as much as we should care for our bodies, we should pay even more attention to our minds and spirits. For they, like lamps of oil, will grow dim with time if not replenished.” (36)

A healthy mind in a healthy body (mens sana in corpore sano) was a common Latin saying, and it is still true today, more than two millennia later. The best medical science of the 21st century agrees: exercise both body and mind throughout your life and not only you will enjoy your youth, you will also find yourself in a much better position in old age.

Again, we are not talking miracles here, and indeed beware of any miraculous remedy for old age (or for anything else, for that matter). If it sounds too good to be true, it very likely is! And let us keep in mind that there will always be exceptions. We all heard about the jogger who died young of a heart attack, or the heavy smoker and drinker who gingerly made it into his late 80s. But those are unusual cases. The statistical trends are very clear and do not afford much room for self-delusions.

“Surely the respect given to old age crowned with public honors is more satisfying than all the sensual pleasures of youth. But please bear in mind that throughout this whole discussion I am praising an old age that has its foundation well laid in youth. … Wrinkles and gray hair cannot suddenly demand respect.” (61-62)

We often hear that age brings wisdom. No, it doesn’t. Not by itself, at least. Mindful aging brings wisdom. That is, wisdom is the result not just of experience—as necessary as the latter is—but of critically reflecting on and learning from one’s experiences. That’s why Cato is saying that wrinkles and gray hair don’t demand respect on their own, and that the foundations of a good old age are, once again, laid throughout our lives.

In terms of honors being accorded to the elderly, of course this depends on the attitude that a given society has about aging. Nowadays we are well aware of the phenomenon of agism, that is, discrimination against older people. It could be found in antiquity as well. One story tells us of an elderly man entering a theater in Athens and nobody willing to give him a seat. He then moved to the area occupied by some visiting Spartans, who all got up and offered him a place. The spectators who saw this bursted into applause, to which one of the Spartans commented that the Athenians obviously know what is right, they are just not willing to do it…

“It seems to me that you have had enough of life when you have had your fill of all its activities. Little boys enjoy certain things, but older youths do not yearn for these. Young adulthood has its delights, but middle age does not desire them. There are also pleasures of middle age, but these are not sought in old age. And so, just as the pleasures of earlier ages fall away, so do those of old age. When this happens, you have had enough of life and it is time for you to pass on.” (76)

The Stoics taught that we should live in agreement with nature. And nature tells us that death is a natural process, an inevitable part of every life. The point, therefore, is not to live as long as possible, or to foolishly fight against the inevitable, but rather to enjoy what nature has given us, while we actually have it.

I am struck by Cato’s comment about running out of pleasures at any age, and that when this happens during the last stage, it is time to move on without regrets. In the meantime, let us focus on living the best life we can, including in old age.

[Next in this series: How to win an argument with Cicero. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII.]

You did it again Massimo……what a fantastic and very timely article. Thank you, thank you for everything you provide. 🙏🏻

I grew up in communist Poland and when I moved from Warsaw to Milan, it turned out that my peers were not so much my peers. I found myself more with the elderly, the post-war generation. People like me who didn't have everything when they were growing up but were very grateful for the little they had. So with my Italian peers, I felt old. Our physical age does not always correspond to our inner age.