[Based on How to Be Content: An Ancient Poet’s Guide for an Age of Excess, by Horace, translated by Stephen J. Harrison. Full book series here.]

Some of you might remember a scene in Dead Poets Society, the 1989 movie directed by Peter Weir featuring a young and brilliant Robin Williams. John Keating, the teacher played by Williams (based on a real person), has brought his class in front of a display of sports trophies and old pictures featuring previous students at the school. Keating has one of his students read out part of a Latin poem, including the famous line:

Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero.

Which translates to: “Harvest the present day, trust minimally in the next.” Though the student in the movie goes for the more common rendition of carpe diem as “seize the day.”

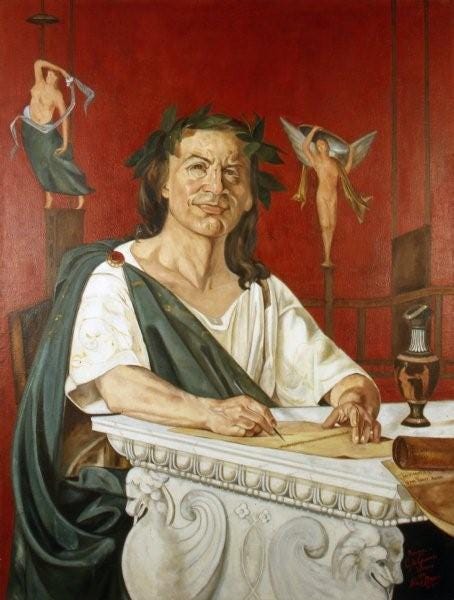

Those lines come from Odes 1.11 by the Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus, commonly known as Horace. Keating/Williams wants to impress on his young students that even though they are currently full of hormones and feeling invincible, one day soon they will be, as he puts it, fertilizing daffodils. If they want to make a mark, if they want their lives to mean something, they better start right here, right now.

Horace was an Epicurean, and I consider myself a (somewhat skeptical) Stoic. And yet, just like the translator of How to Be Content, Stephen Harrison, in my middle age-ish the calm and mature moral advice of Horace resonates convincingly.

Horace was born on 8 December 65 BCE in Venusia, in southeastern Italy, and died on 27 November 8 BCE in Rome, aged 56. That makes him a contemporary of Cicero (who died in 43 BCE) and of the first Roman Emperor, Octavian Augustus (who reigned from 27 BCE to 14 CE).

His life was certainly varied and interesting, fitting the turmoil of the times. His father was a freedman, that is, a former slave, and therefore not in possession of very substantial means. Nevertheless, he managed to send Horace to study first in Rome and then in Athens (where he hung around with Cicero’s son). In 43 BCE the future poet became attached to Marcus Junius Brutus, the chief conspirator against Julius Caesar, serving under his command in Greece as military tribune. That meant that the following year Horace found himself on the losing side at the battle of Philippi.

He escaped and returned to Rome, but lost the family estate to the winning party in the civil war. So he turned to poetry for a living, naturally. He eventually became clerk to the quaestor, which was a significant administrative position, and by the end of the 30s BCE he had enough money to enter the Equestrian order, the one ranking just below the Senate.

Horace attached himself to the circle of Maecenas, a patrician associated with Augustus, who sponsored a number of artists, poets, and writers in Rome. (Indeed, the term “mecenate” in modern Italian means philanthrope). He was introduced by Maecenas by his friend Vergil, himself arguably the most important poet in Roman history. By way of these connections Horace eventually became close to the emperor.

His poetic career lasted three decades and was very much philosophically informed. Horace says (in Satires 1.1.24) that his goal is ridentem dicere verum, “to utter the truth with laughter.” In Epistle 1.2.1-31 he claims that the moral teachings of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are more profound even than those of philosophers like the Stoic Chrysippus and the Platonist Crantor.

The style of Horace’s poetry is inviting in part because he always casts himself as flawed and just as much in need of instruction as his readers, which establishes a relationship of parity with us, rather than one of master-to-pupil. Nevertheless, he tackles head on a number of issues that are still with us today: how to avoid stress, how to live a thoughtful and temperate existence, how to achieve true love and maintain friendships, and how to face setbacks and even death itself with patience and courage.

Harrison’s translation, part of Princeton Press’s Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series, is particularly interesting because it samples a number of poems by Horace arranging them by general theme, making the result a very practical guide to the poetic philosophy of this Epicurean who was often inspired by another great Roman poet, Lucretius.

Here are some highlights from How to Be Content, with accompanying brief commentaries:

“Happy are the traders,” says the soldier weighed down with years,

His limbs now shattered with many a struggle;

The trader, for his part, when the storm winds shake his ship, says:

“Military service is better: what is there to it? There’s a charge:

In the brief space of an hour there comes rapid death or the joy of victory.”

The farmer is applauded by the expert in equity and statute,

When at cock-crow his client knocks on his door;

But the farmer, when dragged from country to city after standing surety,

Proclaims that only those who live in the city are happy.

(Satires 1.1.1–26)

Horace is referring to a vice called by the Greeks mempsimoiria, when one criticizes one’s own lot in life and envies that of others. Today we would say that the neighbor’s grass is always greener, but the basic concept is the same.

The Stoics would agree. It is foolish to envy others, as envy is a matter of our own attitude, which we can change so that we do not add self-imposed misery to whatever objective condition we are in. Moreover, of course, mempsimoiria is also based on bad reasoning. If other people’s grass is greener, and yet those people think that my grass is greener, someone is surely mistaken…

If we are meant to live in accordance with nature,

And we are to begin by seeking a site for building a home,

Do you know any place to be preferred to the blessed countryside?

Is there somewhere where winters are warmer, where a more pleasing breeze

Tames the madness of the Dog Star, and the influence of the Lion,

So wild once it has received the piercing rays of the sun?

Is there a place where envious care disrupts sleep less?

Does the grass have less scent or shine than floors of African marble?

Is the water that on city blocks strains to burst the lead piping

Purer than that which hurries along in a downward stream?

(Epistles 1.10.12–33)

Notice the reference to living in accordance with nature, a guiding principle that was shared by Epicureans and Stoics, and which however meant very different things to practitioners of the two schools. According to Epicurus, nature teaches us that pleasure is good and pain bad, from which he concluded that a good life is the result of avoiding pain and seeking pleasure. That is, in a classic Epicurean fashion, what Horace is doing in the above passage: move to the countryside where you are literally closer to nature, where pain can be avoided without much effort (allegedly), and where the simple pleasures are easy to obtain.

The Stoic take is quite different: while it is true that pain is against nature and pleasure in agreement with it, this is not unique to human beings, but true for every animal species. What differentiates us, what uniquely characterizes human nature, is that we are social animals capable of reason. So to live according to nature, for a Stoic, means to use reason to solve problems and to live cooperatively with other human beings. That, I suggest, is best done in cities, which are also a unique feature of human existence.

This one lives too stingily: let him be called “careful,”

This one’s a fool and a little too likely to boast:

He needs to be seen as “clever” by his friends.

This one is too fierce and over-free in his ways:

Let him be thought “honest” and “strong-minded.”

This one is too hot-tempered: let him be classed as “sharp.”

As I see it, this is what joins friends and keeps them joined.

(Satires 1.3.25–54)

The importance of friendship is another point of contact between Epicureans and Stoics, though again the devil is in the details, so to speak. What Horace is advising here, however, would readily be subscribed to by a Stoic: the way to keep friends is to pass over their defects, in the hope that they will return the favor. Rephrasing, at least in our mind, the characteristics of our friends, is a helpful exercise in tempering our judgments that allows us to work toward general harmony.

A big difference in the way Epicureans and Stoics saw friendship is that for the first ones it was clearly instrumental: I value you as a friend because I derive pleasure or other forms of utility from our relationship. The Stoics rejected that way of looking at friendship, thinking that a true friend is someone we love for their own sake, not for whatever advantage they may bring to us. Aristotle, in contrast with both of the other schools, struck a compromise by suggesting that there are different types of friendship: of utility, of pleasure, and of virtue. The first two are recognized by the Epicureans, the third one by the Stoics.

Forbear to ask what will be tomorrow

And count as gain any day Fortune grants,

And do not, my boy, reject

Love’s sweetness or dancing’s measures,

While gloomy grey age stays away

From your green glow.

(Odes 1.9)

The point here is that the passion of love, to which the ode is dedicated, is a thing for young people, and that it is natural and right that they take advantage of it—at least from an Epicurean perspective. However, in other odes Horace takes up less attractive aspects of love, including jealousy and betrayal, but also the need to reconcile with one’s lover.

The topic of love and the closely associated one of lust brings up the treatment that the various Greco-Roman schools made of the emotions. The Stoics famously distinguished between eupatheiai, or healthy emotions, and pathē, on unhealthy emotions. The root of that distinction is that the first ones are in agreement with reason while the second ones are not. And the Stoic prescription is that we should cultivate the eupatheiai and minimize the pathē. As you might imagine, mature love falls into the category of healthy emotions, while lust and youthful passion are in the category of unhealthy emotions.

Of course, both classes of emotions are “natural,” meaning that they regularly occur in the human animal. But remember that to live in agreement with nature, as I wrote above, doesn’t mean that whatever is natural is good, it means to exercise reason in order to live harmoniously with other people—because the two distinctive characteristics of humanity, according to the Stoics, are rationality and prosociality.

Even though the Epicureans where a bit more permissive than the Stoics with regards to the passions, and even though of course they thought that living according to nature means to seek pleasure and avoid pain, virtue was still a crucial component of their view of the good life. The pursuit of pleasure is to be carried out under the guidance of virtue, otherwise one risks being controlled by one’s pleasures, a situation that is likely to ultimately result in a lot of pain.

You will have to leave the pasture you purchased,

Your town house and your villa lapped by the Tiber,

And your heir will take possession of the wealth

You have built to such a height.

It makes no odds if you are rich and spring

From Inachus of old, or whether you are poor

And of humble family in your stay under the sky,

You victim of Hades who has no pity:

We are all herded the same way, for all of us

Our lot is shaken in the urn, destined to leap out

Sooner or later, and to load us

On the boat to eternal exile.

(Odes 2.3)

The final topic tackled by Horace is the end that awaits us all. Death is the great equalizer, as they say, and it makes no difference whether one is rich or poor, smart or a fool, educated or not.

Philosophizing, according to Seneca, is one long preparation for the ultimate test of our character: facing our own demise. The Stoics and the Epicureans here wholeheartedly agree that there is no reason to fear death, proposing two arguments to reflect on.

First, where death is, we are not, and vice versa. That is, death is the cessation of all conscious activity, so in a literal sense we will not be there to experience it, because there won’t be any “we” there in the first place. So while one may be concerned with the process of dying, one need not be concerned with death itself.

Second, the so-called symmetry argument: why are we so bothered by the thought of non-existing for an eternity after we die, while at the same time we are not at all disturbed by the symmetrical thought that we did not exist for an eternity before being born? The difference between the two situations is not one of factual matters, but only one of human judgment. Which is why Epictetus tells us:

“People are troubled not by things but by their judgments about things. Death, for example, isn’t frightening, or else Socrates would have thought it so.” (Enchiridion 5a)

[Next in this series: How to be a bad emperor with Suetonius. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII.]

Somewhat off topic, perhaps, but how do we get "Horace" out of Quintus Horatius Flaccus? How would he have been referred to by his contemporaries? Quintus? Horatius? Flaccus? Or some combination?

I forgot to mention - the clip you included from Dead Poets Society - Robin Williams’ detailed teaching of his schoolboys about life and death - such graphic, important reminders for us all!