Stoicism began around the year 300 BCE in Athens, a new Hellenistic philosophy established by Zeno of Citium, a Phoenician merchant. But of course Stoicism didn’t come out of nowhere. The most immediate influence was Cynicism, particularly since Zeno’s first teacher in Athens was the famous Crates of Thebes, himself a student of the legendary Diogenes of Sinope. Moreover, the forefather of both Cynicism and Stoicism was Socrates, and in fact the Stoics themselves openly referred to their philosophy as Socratic. Not to mention that Zeno also studied with the Megarian Stilpo, the Dialecticians Diodorus Cronus and Philo, as well as with Xenocrates and Polemo from the Platonic Academy.

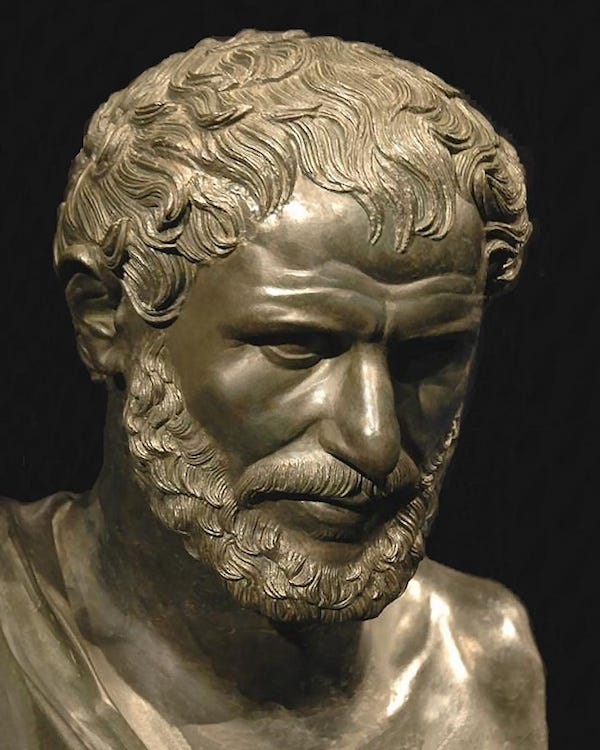

Still, there are more ancient influences on Stoicism, and perhaps the most important, as well as the first one of which we have knowledge, is the Presocratic philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus (535–475 BCE). As it happens, I’ve been reading a wonderful introduction to all the known Presocratics (as well as to the much maligned Sophists), The First Philosophers, by Robin Waterfield (Oxford Classics), which includes a new translation by the author of the known fragments. I highly recommend the book for anyone interested in the beginnings of Western philosophy, but I will focus here on Heraclitus, who had a major impact on the Stoics, and particularly on Marcus Aurelius. (See the excellent annotated edition of the Meditations, also by Waterfield).

The good news about Heraclitus is that he is the first Presocratic of whom we have extended fragments. The bad news is that his style was known to be rather obscure even in antiquity. He did not write books, but aphorisms, probably because the form was more suitable to what was, after all, still largely an oral culture (let’s not forget that Socrates himself refused to write down anything because he distrusted books—thank Zeus for Plato!).

Heraclitus is famous for a number of important themes running through his philosophy, and which influenced not just the Stoics, but several other schools, including a modern approach called process metaphysics.

The first of these themes is that of the Logos, a word that Heraclitus used in a variety of manners. Most comprehensively, it is the rational principle embedded in the functioning of the universe. For Heraclitus, as for the Stoics and many other ancient thinkers, the cosmos was a living organism endowed with reason. That model has, of course, been replaced first by the mechanistic one of Galilean-Newtonian physics, and more recently by the weirdness of quantum mechanics. Even today, though, we have to recognize that the world is, indeed, organized according to rational principles (what is sometimes referred to as “Einstein’s God”), even though we still don’t have much of a clue of where those principles come from. Heraclitus chided his fellow human beings for being capable of understanding the reality of the Logos, and yet sleepwalking through life as if they were incapable of using their own faculty of reason.

A second theme highlighted by Waterfield is that things are relative, in the sense that they change from day to day and context to context. This leads Heraclitus to be somewhat skeptical about human knowledge, but only up to a point. We don’t have a choice but to rely on our senses, even though they are fallible, and the best counter to such fallibility is the development of a faculty of critical judgment. Excellent advice even two and a half millennia later.

Relativity in Heraclitus is closely linked with his idea that everything is in flux, panta rhei (everything flows) as he famously put it. We never step into the same river twice, because the river changes constantly. And yet, at bottom, there is, in fact, a river, which is why one way to understand Heraclitus is to think that he saw no contradiction between an appearance of constant change and the notion of a fundamental unity of the underlying reality. This is pretty sophisticated stuff, connected, as I mentioned above, to the modern idea of process (as distinct from object) metaphysics: what appear to be stable objects to us are really dynamic processes, where the change happens at a scale that is not observable by the human eye.

The third theme, perhaps one of the most puzzling ones, is the notion of a fundamental role of fire in the makeup of the universe. Heraclitus probably didn’t literally mean that everything is made of fire, but he did originate the Stoic doctrine that the cosmos cyclically begins and ends in a universal conflagration, a sort of Big Bang <> Big Crunch ante litteram.

Heraclitus, unlike the Stoics, believed that good people would be rewarded in the afterlife, and that the soul—which is co-extensive with the universe itself—survives death (again, contra the Stoics).

As Waterfield points out, he was essentially the first moral philosopher of the Western tradition, and his ideas about the human ability to reason meant that we make our destiny: the world is characterized by both flux and inner stability, and we are the ones who have the choice to either go through life asleep or to wake up to the reality of the cosmos.

Here are some of my favorite quotes pertaining to Heraclitus’ philosophy, from the fragments translated by Waterfield, to give you a flavor of the ancient texts:

“Of this principle [the Logos] which holds forever people prove ignorant, not only before they hear it, but also once they have heard it. … The general run of people are as unaware of their actions while awake as they are of what they do while asleep.” (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Professors 7.132)

“If you do not expect the unexpected, you will not find it, since it is trackless and unexplored.” (Clement, Miscellanies 2.17.4.4–5)

“It is not better for men to get everything they want. Disease makes health pleasant and good, as hunger does being full, and weariness rest.” (John of Stobi, Anthology 3.1.176, 177)

“Everyone has the potential for self-knowledge and sound thinking.” (John of Stobi, Anthology 3.5.6)

“On those who step into the same rivers ever different waters are flowing.” (Arius Didymus, fragment 39)

“Heraclitus says somewhere that everything gives way and nothing is stable, and in likening things to the flowing of a river he says that one cannot step twice into the same river.” (Plato, Cratylus 402a8–10)

“The reason it is hard to fight against passion is that it buys what it wants at the expense of the soul.” (Plutarch, Life of Coriolanus 22.2.5–6)

“Man’s character is his guardian spirit.” (John of Stobi, Anthology 4.40.23)

Quantum Field Theory might be regarded as closer to Heraclitus than Democritus.

Though QFT is perhaps more radical. A state is a superposition of all the possibilities at the same time but is not changing in time (unless something happens).