Five insights about character

A few life-changing tips for those who wish to become better human beings

Character, specifically my own and how to improve it, has been at the forefront of my thinking for a number of years now. After all, the betterment of one’s character is one way to describe the major goal of Stoicism, or of any Greco-Roman philosophy (and, arguably, of many other philosophies, like Confucianism).

That’s why last year I published a book on the subject, The Quest for Character: What the Story of Socrates and Alcibiades Teaches Us about Our Search for Good Leaders. In a sense, the book puts together much of what I’ve learned about character from both a philosophical and a scientific standpoint (“sci-phi,” if you will), applying it not just to the question of what makes a good leader, but more broadly the question of what makes for a good human being.

The Quest for Character examines the issue using examples from Greco-Roman antiquity, for two reasons. First, because human nature hasn’t changed, and some of the insights of the best of our forerunners are just as good as those of any modern psychologist or sociologist. Second, because it’s easier to learn from other people’s examples if those people are sufficiently removed from us that we don’t really have an emotional stake in whether they were right or wrong, good or bad.

While you will forgive me for also suggesting to read the actual book, here are the five major insights I have arrived at while writing it. Hopefully they’ll be useful to you in your personal quest for ethical self-improvement.

Insight n. 1: Virtue can (and should) be taught

Nowadays when we hear talk of virtue we tend to think of old fashioned Victorian characters, or perhaps of the Christian virtues of hope, faith, and charity. But the word “virtue” comes from the Greek arete, which means excellence. So a virtuous person is an excellent person, the best person they can be.

What does that mean? The ancient Greco-Romans thought that being excellent means performing one’s function well. For instance, I recently bought an excellent bread knife. Meaning a knife that does well what it is supposed to do: cut bread.

By analogy, an excellent human being is one who does well what human beings are designed by Nature to do. Since our distinctive characteristics are that we are highly intelligent and highly social animals, our natural function is to use our brains to solve problems, and to do so in a socially cooperative fashion. That’s how we survive and flourish as a species. It’s not just the ancients who say so, this view of humanity actually jibes well with the discoveries of modern primatologists and evolutionary biologists. Large brains are our chief evolutionary weapon, and social living is a crucial characteristic of our species.

According to the Greco-Romans, virtue understood as human excellence is a skill (techne) and therefore can be taught, just like any other skill. Imagine you wished to learn a musical instrument, or maybe a new language. How do you go about it? You will learn some basic musical theory or grammar; you will get a good teacher who can guide you; and then you’ll practice, practice, practice. The same goes for virtue: you become a better person by learning a bit about ethics, by following a good teacher like Socrates, and by doing a lot of practice.

But how, exactly, do you practice virtue? Suppose that you feel like you are not generous enough, for instance. One way to improve at this might be to get into the habit of putting some change into your pocket before leaving your house, and then give that money to the first homeless person you encounter—no questions asked. This will initially be awkward, perhaps embarrassing even. But the more you do it, the more it will become second nature. And you’ll soon be on your way to becoming a more generous person.

Insight n. 2: If you are not virtuous, don’t get into politics

The subtitle of The Quest for Character is “What the Story of Socrates and Alcibiades Teaches Us About Our Search for Good Leaders.” That’s because that particular story provides the starting point for my project. And it is a story well worth knowing.

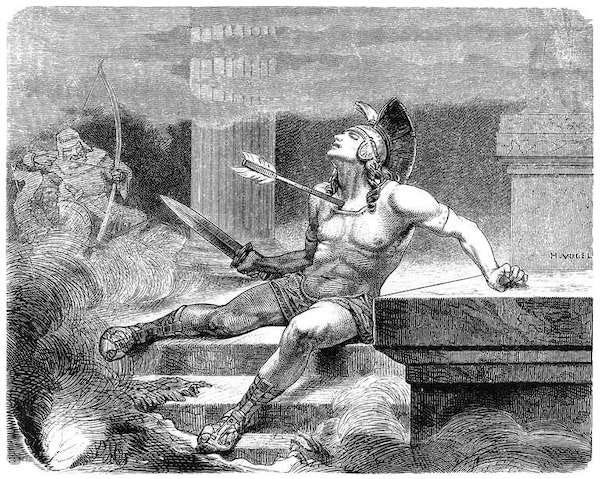

Alcibiades was a friend and student of Socrates. He was impossibly handsome, uber-rich, brave, and descended from one of the noblest families in Athens. In other words, he had everything one might want in order to become a leader. Except a good character.

Alcibiades goes to Socrates to ask for advice, and the philosopher basically subjects the young man to a job interview, where the job is leading Athens in the middle of the Peloponnesian War against its rival, Sparta.

Socrates pretty quickly figures out that Alcibiades does not have what it takes. He is too narcissistic, wanting to be a leader not for the good of the people, but to engage in self-aggrandizement. Does that ring a bell? Does it perhaps remind you of some modern leaders? At one point Socrates lays it out clearly and bluntly to his friend. He says:

“Then alas, Alcibiades, what a condition you suffer from! I hesitate to name it, but it must be said. You are wedded to stupidity, best of men, of the most extreme sort, as the argument accuses you and you accuse yourself. So this is why you are leaping into the affairs of the city before you have been educated.” (Plato, Alcibiades I)

Ouch. The Greek word usually translated as “stupidity” is amatia, which is perhaps best rendered as “unwisdom.” Socrates is saying that Alcibiades lacks the wisdom necessary to run the country. Unfortunately, Alcibiades did not follow Socrates’ advice, went into politics anyway, and—predictably—led Athens to final disaster. The moral of the story: don’t get into politics unless you have a good character and good motivations.

Insight n. 3: A good character is an inside job

The Quest for Character examines a number of case studies from the ancient world, both of politicians that were advised by philosophers, as well as of statesmen who practiced philosophy as a way of life of their own accord. On balance, it turns out that when someone is not receptive to external advice, they will not fare well as statesmen. By contrast, when a future leader grows up wanting to be a good person and working on behalf of others, then they do much better.

For instance, Plato, the most well known of Socrates’s students, tried to instill virtue in Dionysius the Second of Syracuse, in Sicily. He failed abysmally, because Dionysius was simply not interested in anything other than self-serving behavior. In fact, Plato almost lost his life in the endeavor.

By contrast, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius really did try to govern in the best manner possible, and he was guided in his efforts by his chosen philosophy of Stoicism. The important difference with Dionysius is that Marcus wanted to do good, and realized that listening to his philosophical mentor—a Stoic named Junius Rusticus—was important.

Modern scientific research supports the intuitions of the Greco-Romans: while we can effectively teach ethics to young children, because their brains are not yet fully formed, only adults who are interested in self-improvement will be receptive to such teachings. Again, it’s like learning a musical instrument or a language: much easier if done early in life, though even old people can still do it, if they want to.

Insight n. 4: We should all be “philosophers”

These days philosophy tends to get a bad rap. Philosophers are imagined by people to be stuffy academics who spend their time engaging in navel gazing, thinking deep thoughts about abstruse matters nobody else cares for. There is, unfortunately, some truth to this view. But a philosopher, in ancient Greece and Rome, was someone who practiced the art of living, that is, who used critical thinking and wisdom in order to navigate life’s challenges.

In that sense, anyone can be a philosopher, no PhD required! All you need to have is a functional brain and the willingness to use it. A philosopher of this kind will spend most of their time actually living life in the here and now, paying attention to the world and the people in it, and constantly trying to handle situations in the best way possible.

A philosopher of the sort we are talking about will use the four cardinal virtues as a moral compass of sorts: practical wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance.

Practical wisdom is the knowledge of what truly is, or is not, good for us. (Regardless of what others, or society at large, may tell us.)

Courage is the willingness to act in the right manner even when there is a personal cost.

Justice means to treat others fairly and with respect, the way we would like to be treated.

And temperance means to act in right measure, neither too much nor too little.

For instance, suppose I walk into work and find my boss harassing a co-worker. Should I intervene? How? I consult my moral compass.

Practical wisdom tells me that it is good for my own character to be helpful to others, because it makes me a better person.

Courage is required because my boss may retaliate.

Justice says that I should intervene because if I were the one being harassed I very much would like to have someone help out and diffuse the situation.

In terms of temperance, my intervention should be proportionate to the situation. I don’t need to start punching my boss, for instance; but I also can’t just whisper something under my breath and call it a day. I need to step in firmly but gently.

The radical Greco-Roman idea is that if we all tried to live like philosophers in this sense, the world would be a much better place. So, be a philosopher!

Insight n. 5: What works and doesn’t work when it comes to improving our character

As we have seen, improving our character is a skill. But what sort of things work or don’t work when it comes to becoming a better person? Let’s start with what doesn’t work.

For one thing, doing nothing doesn’t work. You often hear that people become wiser as they get older. But that’s not really the case. There are a lot of cranky old people out there who are not wise.

Age is necessary in order to become wiser, but it isn’t sufficient by itself. It’s necessary because wisdom is acquired by experience—just like playing well a musical instrument is something that requires a lot of practice. But it has to be mindful practice: we need to pay attention to what happens to us and why, and actively try to learn from our experiences.

A second thing that doesn’t work is actually very popular these days: nudging. If you are a man you have seen public urinals with a fly drawn where you are supposed to hit. That’s an example of nudging: someone designs a system that effectively manipulates people’s behaviors in a desired direction.

But nudging does not improve character since it isn’t designed to do so. You will hit the fly not because you are convinced that it is good not to urinate on the floor; you’ll hit the fly because now you are engaged in a game. Your motivation, in other words, is not the right one.

A third thing that doesn’t work is virtue labeling, you know, as when you tell your child that he is brilliant even though he clearly isn’t. Repeating the lie for encouragement will not make him brilliant. Study hard might.

What does work in order to develop a better character? For instance, adopting a role model. Pick someone you admire, regardless of whether you know them or not. Pick Socrates, or Buddha, or your grandmother. It doesn’t matter who you choose, so long as you always ask yourself the crucial question: “what would my role model do?”

That’s what the ancient Greco-Romans did, and empirical evidence from modern science shows they were right: people tend to behave more ethically if they get into the habit of thinking about their role model.

Another thing that works, if we want to become better people, is to keep track of our own progress. It’s called philosophical journaling, and a very good example is provided by Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations. In the book, which was really his personal diary, the Roman emperor critically examined his own behavior, repeatedly prodding himself to do better.

For example, let’s say you had an altercation with your partner today. What did you do wrong? What did you do right? And what could you do better next time that something like this happens? By paying attention to both your mistakes and your successes, and by preparing your mind for future occurrences, you gradually become better at the business of life.

One more thing that works is to purposely seek out situations that train you to improve your character. For instance, let’s say you realize that you are a bit deficient in temperance. Well, then, the Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus pointed out that we have at least three occasions daily to practice our temperance: every time we sit down to have a meal.

Before you start eating, remind yourself that you don’t just want to nourish yourself and enjoy good food. You also want to improve your character. Then visualize ahead of time how much food and drink is reasonable, and try to stick with it throughout the actual meal.

It’s okay if you slip up. You can notice the mistake and correct it the next time around. The idea, which goes back to Aristotle and the Stoics, is that, in a sense, you fake it until you make it. Initially the behavior will feel awkward, but you’ll soon get used to it, and it eventually will become second nature.

Those are some of the insights from The Quest for Character. Let me leave you with an appropriate quote from one of my favorite Stoic philosophers, Seneca, about whom I write in the book. He said:

“Fortune has no jurisdiction over character.” (Letter 36.6)

Meaning that improving your character is up to you, while other things—like health, wealth, and reputation—are ultimately the result of external factors that you don’t control.

Work on your character, and you’ll be in charge of what really matters in your life.

I have so enjoyed your wise words. Many thanks! Worth every minute!

Thank you for the summary Massimo, as it's still not available in Kindle in Australia. In case you're not aware of it, this rather simplistic critique of Stoicism was published in The Conversation today "3 Reasons not to be a Stoic (and try Nietzsche instead)" https://bit.ly/3x0lZNb . He portraits the Dichotomy of Control as advocating for passivity; misrepresents the Stoic methods of managing emotions by saying we avoid experiencing the full range of emotions, especially the negative ones; and asserts that the discipline of assent, as applied to injuries, is somewhat akin to solipsism. I'm sure you & the Modern Stoicism team must get a lot of this.